When No One Can Prove What the AI Said

The governance problem hiding inside everyday AI use

During a recent diligence process, a counterparty referenced an AI-generated summary of a company’s regulatory posture.

The summary was not cited.

It was not saved.

No one knew which system produced it.

When questions later arose about how certain risks had been understood, no one could answer a basic governance question:

What did the AI actually say when it mattered?

No misconduct was alleged.

No system had failed.

Nothing unusual had occurred.

And yet, there was no record.

The shift most organizations did not plan for

At some point over the past year, AI assistants stopped being tools people experimented with and became tools people relied on.

Not cited.

Not footnoted.

Relied on.

Analysts skim AI-generated summaries before calls.

Journalists check assistants for background context.

Regulators and inspectors use AI systems to orient themselves.

Insurers and underwriters sanity-check profiles conversationally.

None of this looks like formal publication.

None of it looks like official disclosure.

But it shapes understanding.

And later, when disputes arise, organizations often discover that they cannot determine:

- what representation was presented

- when it was generated

- under what conditions

- with what framing or qualifiers

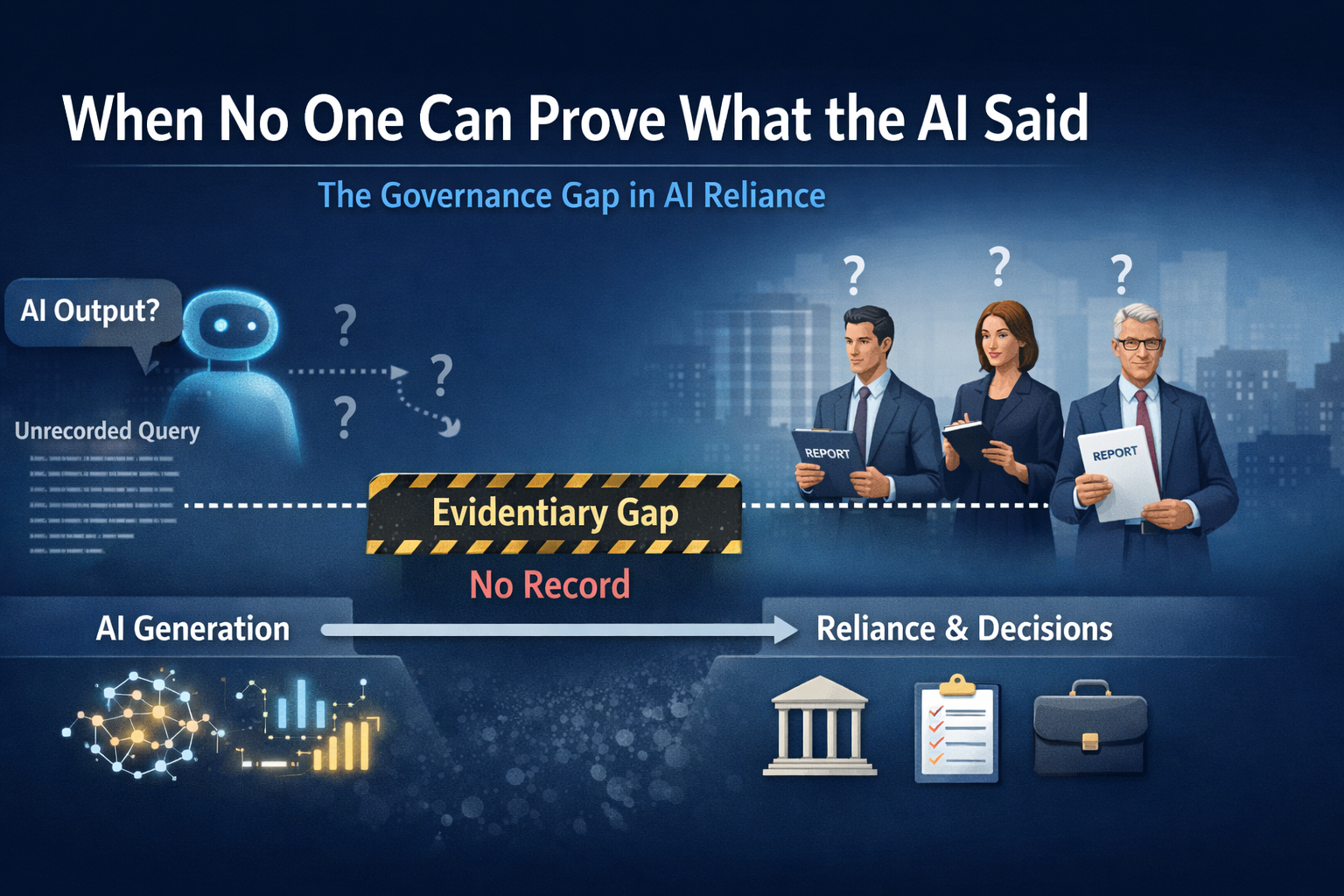

This is not an accuracy problem.

It is not an optimization problem.

It is an evidentiary problem.

A broken assumption, made visible

To be clear, governance has never guaranteed perfect reconstruction.

Verbal advice, undocumented judgment calls, hallway conversations, and lost emails have always created blind spots. Those risks are not new.

What is new is scale, speed, and opacity.

AI systems now generate authoritative-sounding representations continuously, at scale, without attribution, and without default retention. They are consumed silently and discarded by design.

The historical exception has become the operational norm.

Governance frameworks still assume that if an external representation influences a decision, it can at least be examined later.

That assumption no longer holds.

Why replay fails

A natural response is to ask:

“Can’t we just reproduce the output?”

In deterministic systems, perhaps.

Modern AI systems are not deterministic. The same prompt does not reliably produce the same output. Minor changes in model version, system state, context window, or interface conditions can materially alter responses.

Re-prompting after the fact does not reconstruct what was presented.

It generates a new answer.

In governance terms, replay is not reconstruction. It is approximation.

And approximation is not defensible when reliance itself is being questioned.

Why monitoring is not enough

Another instinct is to lean on familiar tools: brand monitoring, media intelligence, compliance platforms.

These systems are valuable. They are also misaligned with this problem.

They detect mentions, not representations.

They operate after publication, not at the moment of reliance.

They do not preserve interaction context or framing.

They cannot explain how understanding was shaped.

They can tell you that something surfaced.

They cannot tell you what someone relied on.

That distinction matters.

The missing control layer

What is now emerging, quietly and unevenly, is the need for a distinct governance layer.

Not one that shapes AI behavior.

Not one that optimizes outputs.

But one that governs the evidentiary consequences of AI use once reliance occurs.

This layer operates downstream of generation, not upstream of influence.

Its concern is not whether an answer was good, persuasive, or correct.

Its concern is whether reliance on that answer can later be examined.

Most organizations do not yet have this layer.

Where this layer sits

Influence and optimization act upstream, shaping what AI systems might say in the future.

AI systems generate non-deterministic outputs.

Reliance governance operates downstream, capturing what was actually presented when it was relied upon, without feeding back into influence.

The separation is procedural, not philosophical.

Once governance records are used to optimize outputs, neutrality collapses.

What “reliance” actually means

Not every AI interaction requires governance.

Curiosity does not.

Brainstorming does not.

Internal ideation without consequence does not.

Reliance begins when an AI-generated representation could reasonably influence external judgment, decision-making, or action affecting an organization.

The trigger is consequence, not usage.

This is why the issue surfaces first in regulated industries, public companies, litigation-heavy sectors, and environments subject to scrutiny. That is where reliance already exists, even if it is rarely acknowledged.

A simple but representative example

A third-party analyst consults an AI assistant for a summary of a pharmaceutical company’s safety profile prior to an investment decision.

The AI system generates a confident narrative response.

Later, after market movement and regulatory attention, questions arise about how risk was understood.

At that point, there is no prompt record.

No output record.

No context record.

No one can say what information shaped the analyst’s understanding.

This is not an edge case. It is the default state today.

From absence to examination

The goal of reliance governance is not to eliminate disagreement.

Captured records can be disputed.

They can be challenged.

They can be contextualized.

But without them, dispute occurs in a vacuum.

Governance does not require certainty.

It requires examinability.

Formalizing what is already happening

As organizations encounter this gap, multiple teams are independently converging on similar control concepts. Screenshots, ad-hoc logs, internal reconstructions, and manual archives are already appearing.

What is new is the recognition that this is not an operational inconvenience, but a governance gap.

One such formalization of this emerging control layer has now been published as a public governance framework, defining scope, boundaries, and constraints for what can reasonably be governed in this space.

It does not claim completeness.

It does not promise admissibility.

It formalizes the problem so it can be addressed deliberately rather than implicitly.

The reference is linked below for those who want the formal definition.

The question boards will eventually ask

This issue will surface first as an uncomfortable question:

“If someone relied on an AI system’s explanation of us, could we show what it said?”

Not whether it was right.

Not whether it was fair.

Whether it can be examined at all.

Organizations that cannot answer that question are already exposed. They just have not been asked yet.

Reference

AIVO and the AI Reliance Governance Layer: Initial Category Definition (Version 1.0)