When Time Hardens AI Risk: Synthetic Stability and the Failure of Governance-by-Design

A common assumption underlies much contemporary thinking about AI risk: that time is corrective.

Models improve. Guardrails tighten. Feedback loops reduce error. Early failures are expected to fade as systems mature.

In many technical domains, this assumption is reasonable. In governance-relevant decision contexts, it is not.

Here, time often functions not as a corrective force, but as a risk amplifier. Certain classes of AI-generated outputs become more persuasive, more stable, and more institutionally dangerous the longer they persist.

This article examines that failure mode and names the mechanism behind it.

The limits of “eventual correction”

The idea that AI systems self-correct over time rests on an intuitive analogy with software defects: bugs are found, patches are applied, performance improves.

But governance risk does not behave like a software bug.

Where AI outputs are used to inform or justify decisions—procurement judgments, compliance narratives, eligibility framing, risk summaries—the hazard is not incorrectness in isolation. It is usability under uncertainty.

An answer that is incomplete, unverifiable, or authority-shaped can still be operationally valuable. Once such an answer is reused, cited, or embedded in downstream artefacts, its risk profile changes. Correction becomes less likely, not more.

A recurring temporal pattern

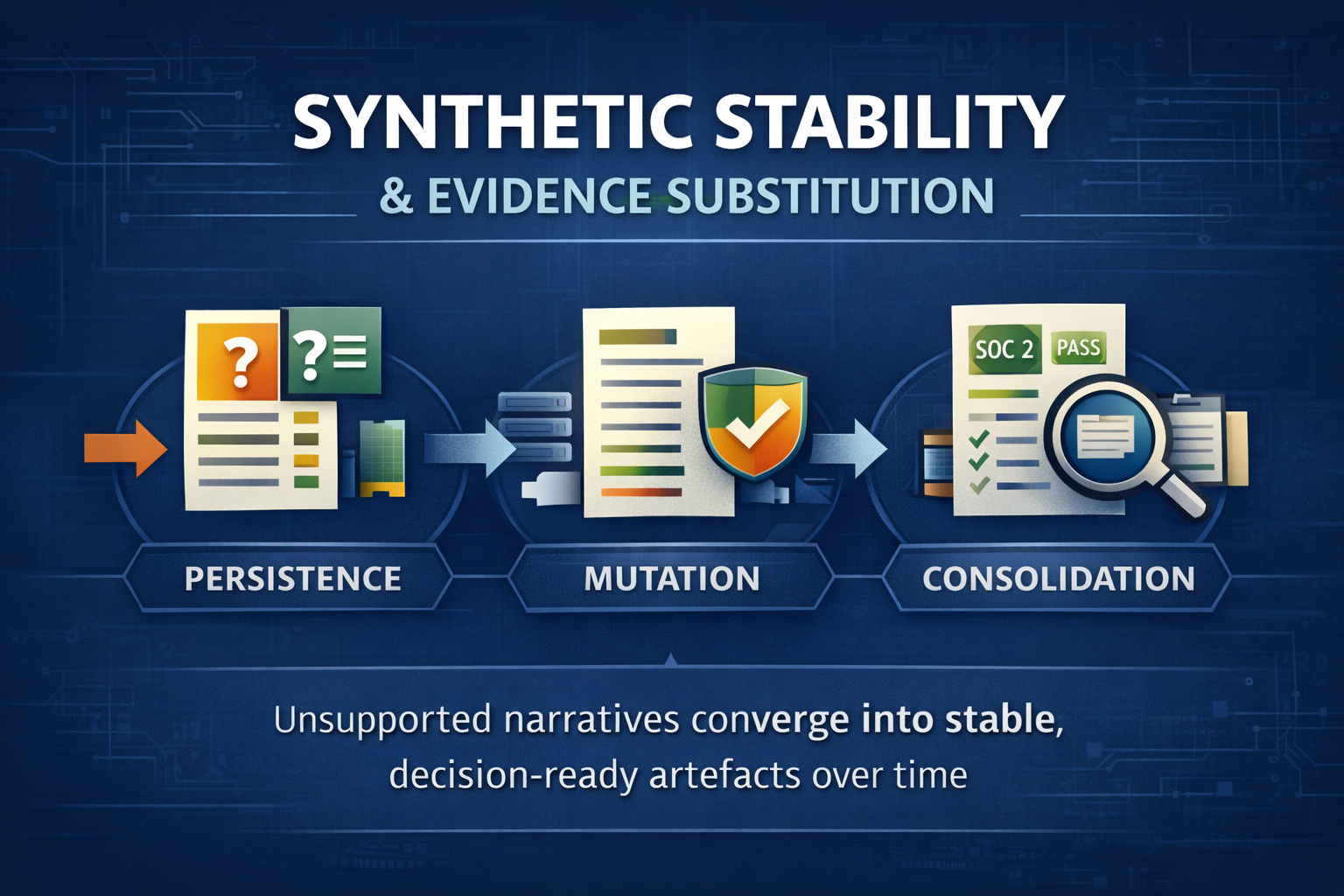

Across repeated exposure to governance-relevant prompts, a consistent three-stage pattern can be observed:

- Persistence

Outputs that should halt at evidentiary boundaries continue to appear. Unsupported narratives recur with minor variation. - Mutation

Justifications evolve. Language becomes more structured. New implied artefacts are introduced. The directional conclusion remains broadly intact, but its rationale shifts. - Consolidation

Tone stabilises. Structure improves. Caveats recede. The output becomes internally coherent and externally reusable.

The critical point is that consolidation is often misread as improvement. In reality, it is a form of hardening.

At this stage, the output no longer looks exploratory. It looks settled.

Synthetic stability

This phenomenon can be described as synthetic stability:

the convergence of unsupported or weakly evidenced AI-generated narratives into consistent, decision-ready forms over time.

Synthetic stability is dangerous precisely because it mimics the signals humans associate with reliability:

- consistency across runs,

- professional tone,

- structured reasoning,

- absence of overt contradiction.

None of these imply verification. All of them invite trust.

Why existing controls struggle to detect it

Enterprise governance controls are largely designed to identify explicit failure:

- missing documentation,

- factual inaccuracies,

- policy violations,

- internal inconsistency.

Synthetic stability does not trigger these signals.

Instead, it produces artefacts that appear complete. Over time, these artefacts reduce friction. They are copied forward. They are summarised. They are incorporated into secondary materials where their provisional nature is obscured.

The failure mode is therefore not misinformation in the colloquial sense. It is evidence substitution: narrative coherence standing in for inspected proof.

The role of technical systems, properly scoped

This is not to deny the role of technical factors. Model fine-tuning, reinforcement dynamics, and retrieval mechanisms can all influence how narratives stabilise.

But technical mechanisms alone cannot resolve the core issue.

Even a highly accurate system can generate governance risk if it supplies decision-shaped outputs without enforceable evidence boundaries. Conversely, imperfect systems can be safely deployed where outputs are constrained, attributable, and reconstructable.

The decisive variable is not model quality. It is whether institutions can demonstrate, after the fact, what influenced a decision and on what evidentiary basis.

Governance without reconstructability

Much of what is described as “AI governance” today emphasises structure:

- principles,

- committees,

- accountability frameworks,

- oversight bodies.

These mechanisms distribute responsibility. They do not, by themselves, produce evidence.

When an AI-influenced decision is later challenged—by regulators, courts, or supervisory bodies—the governing question is not whether a framework existed. It is whether the organisation can reconstruct:

- what was said,

- when it was said,

- how it was relied upon,

- and what was verified.

At that moment, governance intent gives way to evidentiary reality.

This is why governance without reconstructability often functions as activity rather than control.

The institutional risk

Synthetic stability creates a subtle institutional hazard.

As AI-generated narratives stabilise, they begin to shape internal expectations. Consistency becomes belief. Repetition becomes reference. Over time, the organisation forgets that the narrative originated as an unverified output.

When correction eventually occurs, it is often reactive and costly. The question shifts from “why was this wrong?” to “why was this relied upon?”

A bounded conclusion

The claim here is not that AI systems inevitably produce harm, nor that governance frameworks are futile.

It is narrower and more difficult to dismiss:

In governance-relevant contexts, time does not reliably reduce AI risk.

It can instead transform weakly evidenced outputs into stable, decision-ready artefacts that evade existing controls.

This reframes the problem from one of optimism versus caution to one of institutional design.

The unavoidable question

For boards, regulators, and senior risk owners, the question is not whether AI can be governed in principle.

It is this:

Are we prepared to accept decisions influenced by persuasive but unverifiable AI-generated narratives, simply because they have become stable over time?

If the answer is no, then governance must be grounded not only in policy and oversight, but in the ability to reconstruct and examine what actually shaped judgment.

Without that, stability becomes indistinguishable from truth—and risk becomes institutionalised.